MyRadar

News

—

The Science (and Uncertainty) Behind Weather Forecasts

by Will Cano | News Contributor

10/26/2022

It was a cold, dark winter’s night. I was ten years old, and I was sitting in the family room with my Dad in front of the TV as the weatherman was on, displaying a live forecast. Upon meeting my gaze, anyone would have been greeted with eyes full of excitement.

On the screen, a forecast of 12 to 18 inches of snow was displayed for my local region. The snowstorm would strike one week later. I am an avid snow lover, and I was ecstatic for the upcoming blockbuster storm.

For the next week, I checked the forecasts religiously. The morning after seeing the original prediction, an update was released that had bumped our region down to 8 to 12 inches of snow. My happiness didn’t waiver, and I would happily 'settle' for up to a foot of powder.

The next day, however, 5 to 8 inches of snow was forecast. Now I felt some disappointment as I saw an original prediction that had been cut by more than half.

The next morning, the forecast called for 3 to 5 inches that evening. That evening, 1 to 3 inches. Soon, the forecast was down to a measly one inch.

I vividly remember the day that the “storm” arrived. Outside, a light mix of small snowflakes and raindrops drizzled from the sky. Not one flake stuck and no snow accumulated that day.

This story may not sound unfamiliar to many, as we have all experienced times when the weatherman on TV misses an upcoming forecast that’s important to our personal lives. But why do meteorologists get the only profession where they are paid to be supposedly wrong 80% of the time? And how do they come up with these lousy forecasts anyway?

Meteorologists actually deserve a lot less of the slander they get and it may just be time to applaud them for their attempts to predict the future.

To understand how we forecast the weather today, it is first important to determine when people first started to predict weather. As it turns out, humanity has been trying to crack the code for a long time.

Illustrations depicting the ancient civilization of Babylon and Greek philosopher Aristotle. Image Credit: Martin Heemskerck, Literary Theory and Criticism

Around the year 650 B.C., the Babylonians of present-day Iraq were the first civilization to make consistent observations about the weather.

It wasn’t until 350 B.C. when Greek philosopher Aristotle gave weather forecasting an update. Aristotle wrote Meteorologica, a textbook on the weather he observed. The encyclopedia also included theories of how these weather phenomena occurred - from lightning to windstorms to wildfires.

Although much of the information written was false, it was the first major work that those interested in the weather could study.

After Aristotle, a near-2,000 year gap took hold of society attempting to predict the weather. It was then that famous technology used today first came into practice.

Around 1450, the first device used to measure humidity was described. In 1592, Galileo Galilei invented the first version of a thermometer named a 'thermoscope'. By 1643, the first barometer, used to measure atmospheric pressure, was invented.

Some of the first models of weather instruments commonly used today: the hydrometer (left), the thermometer, or 'thermoscope' (middle), and the barometer (right). Image Credit: The University of Oklahoma, Science Museum Group

With these pieces in place, members of the scientific community began to better understand and even predict the weather.

Robert Fitzroy was the first person to make weather “forecasts” in 1859. These began as weather stations and warning systems for different areas of the English coast. In just a few years, however, Fitzroy was credited for the first weather forecasts in the daily newspaper.

So, how have we changed our weather forecasting techniques since Fitzroy? It turns out, we have improved a whole lot. Scientists have developed precise technology that helps us better read our atmosphere, ranging between satellites, radars, and more data-measuring instruments.

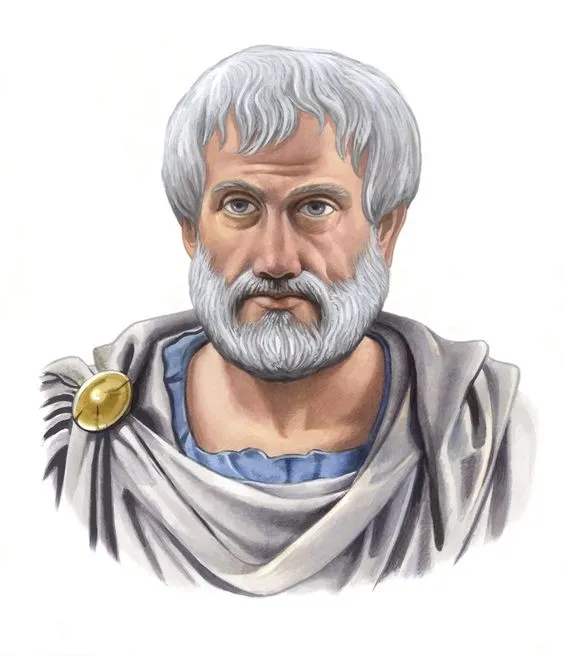

However, one of the most significant understandings that meteorologists have come to realize is how our atmosphere works and interacts with our planet. Gasses in the atmosphere behave more like a fluid than a gas. As a result, physics equations of fluid motion and thermodynamics have been derived to become specific to our weather.

This means that math is at the center of every weather forecast made today. In fact, this math was even given its own name: Numerical Weather Prediction (or NWP for short).

The Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) equation. This math stresses the complexity that goes into every weather forecast. Image Credit: NWS Juneau

This equation’s obvious complexity demonstrates how difficult the weather is to predict. It takes into account the many different laws of physics that rule our planet, ranging from the Conservation of Mass, Energy, and Momentum to Ideal Gas Laws and Fluid Dynamics.

What's more, however, are the assumptions that this equation makes. Our atmosphere is constantly changing, whether it be the air temperature, the humidity, the amount of vegetation on the ground, the reflection of the sun from a certain landscape, or one of the many other unknowns. All of these changes — and how they affect each other — are impossible to account for in math. As a result, hundreds of “assumptions” are made to best model what actually happens, and how it will affect the future weather.

The complexity of our atmosphere adds another layer of proof why the weather is so hard to forecast.

Many factors that change and influence the weather in our atmosphere, leading to meteorological “assumptions”. Image Credit: NWS Juneau

Once all of this data is absorbed, computer software crunches the numbers and outputs a visual representation of what the upcoming weather may look like.

The result is a weather model, which every meteorologist checks multiple times a day to serve as the base of their forecast. The models namely predict where storms (or low pressure systems) may go, but also foretell temperatures, wind speeds/directions, humidity and precipitation accumulation.

However, there are limits to how accurate these models, and thus meteorologists, are. All of these complexities and uncertainties explain why this is true.

NOAA reports that a five day forecast is 90% accurate, a seven day forecast is 80%, and a ten day forecast is about 50% accurate. However, a peer-reviewed research paper by the American Meteorological Society states that these forecasts could improve to become accurate up to fifteen days out in the near future.

The 'final result'. Above is the American, or GFS, weather model, depicting where storms (Red 'L's) and fair weather (Blue 'H's) may travel over the next ten days. The United States is not the only country that produce these weather models, and each weather model differs in their predictions of upcoming storms. An average of all the different outputs are usually created by meteorologists to make the most accurate forecast. Image Credit: Weather Bell

The complexity of forecasting has led to some historic forecasts that are either famous or infamous for their accuracy.

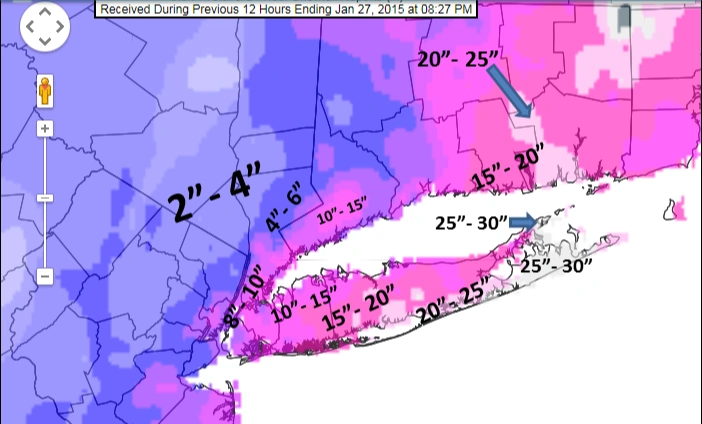

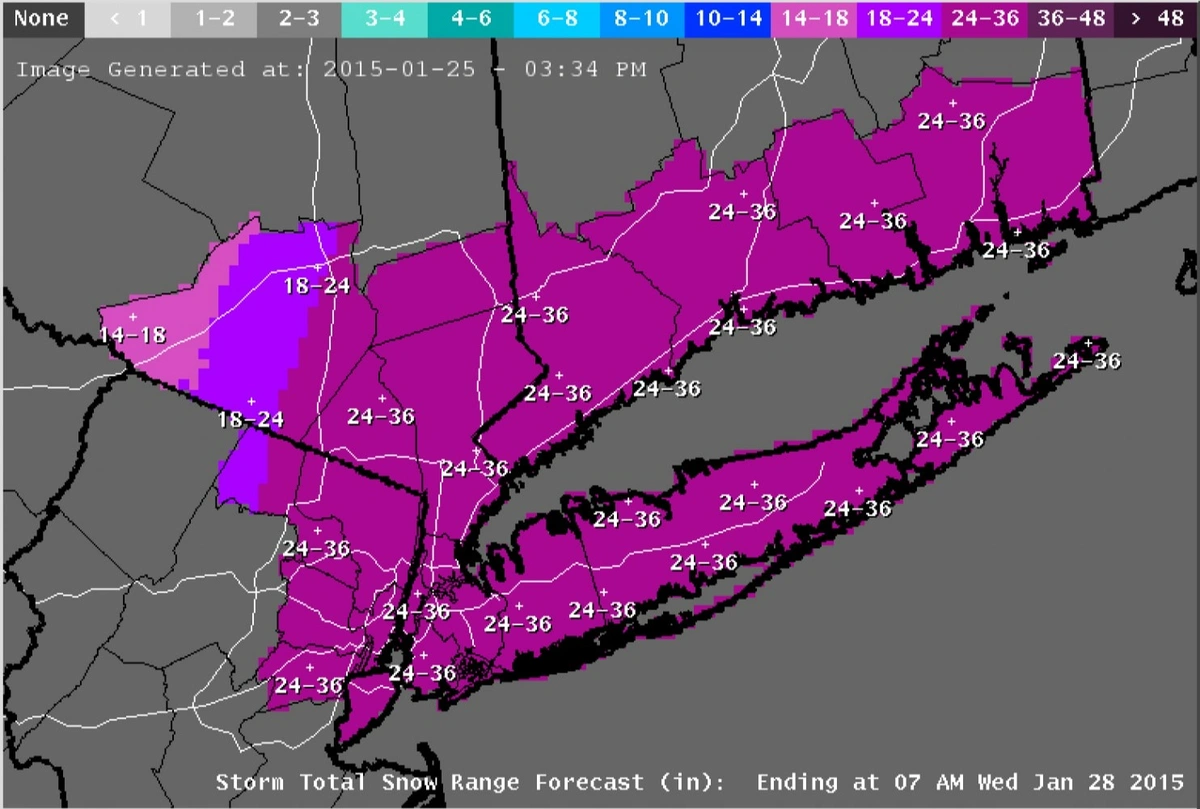

One of the most infamously-botched forecasts in recent history was a Nor’easter Snowstorm in January 2015. It was predicted to blast New York City with up to three feet of snow and blizzard conditions.

Closings of schools and businesses were planned days ahead of the storm. Subway systems were shut down for the first time in city history. It was predicted to be a direct hit, and then-mayor Bill de Blasio warned of ‘something the likes that New York City had never seen’.

In the end, however, a grand total of 9.8 inches fell in Central Park. The storm had shifted to the east by just 70 miles, and the brunt of the storm impacted the tip of Long Island and the Massachusetts tri-state area.

Predicted snow ranges (in inches) for the Blizzard of 2015 in the New York City area. The prediction on the left represents the forecast just one day prior to the storm, while the right shows the actual amounts that fell. Image Credit: NWS New York

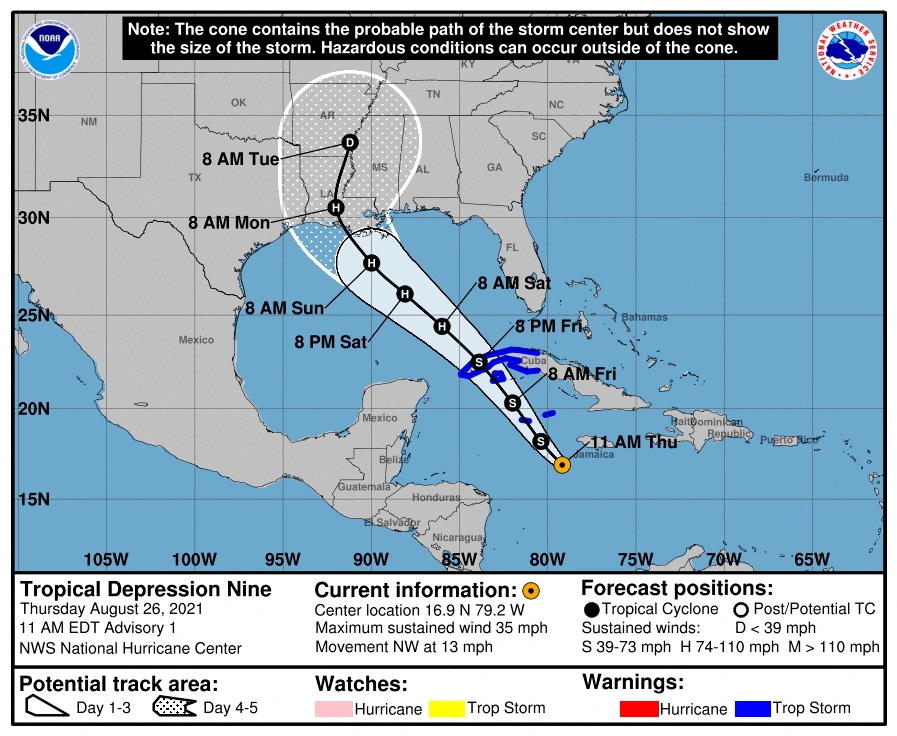

Hurricane Ida, on the other hand, was a forecast of admirable precision. With landfall in the United States still five days away, the first predicted path, with a ‘cone of uncertainty' was released by the National Hurricane Center. Meteorologists stressed that the hurricane would likely track somewhere within this cone, with the most likely track being depicted by the middle.

Five days later, upon making landfall, the storm hit just a few dozen miles to the east of the original prediction. The advanced accuracy of the warnings likely saved many lives in the process.

The Cone of Uncertainty for Hurricane Ida five days prior to landfall (left) compared to the actual path the center of the storm took (right). Image Credit: National Hurricane Center, NWS New Orleans

Meteorologists do get paid to be wrong every now and then, but cut them some slack: they are not dealt an easy task by any means. Next time you are watching the local weatherman give a forecast, you can understand a little bit more about what’s going on behind the scenes. Personally, I've learned not to be so confident in a seven-day forecast like I was on that winter's Sunday night.